Ambushes and Massacres

Early American Massacres

1622 - Jamestown Massacre

The  Indian massacre of 1622 took place in the English Colony of Virginia on March 22, 1622. The English explorer Captain John F Smith, though he was not an eyewitness, wrote in his History of Virginia that warriors of the Powhatan "came unarmed into our houses with deer, turkeys, fish, fruits, and other provisions to sell us." They then grabbed any tools or weapons available and killed all of the English settlers they found, including men, women, and children of all ages. Opechancanough, paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy, led a series of co-ordinated surprise attacks that ended up killing a total of 347 people, a quarter of the population of the Colony of Virginia.

Indian massacre of 1622 took place in the English Colony of Virginia on March 22, 1622. The English explorer Captain John F Smith, though he was not an eyewitness, wrote in his History of Virginia that warriors of the Powhatan "came unarmed into our houses with deer, turkeys, fish, fruits, and other provisions to sell us." They then grabbed any tools or weapons available and killed all of the English settlers they found, including men, women, and children of all ages. Opechancanough, paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy, led a series of co-ordinated surprise attacks that ended up killing a total of 347 people, a quarter of the population of the Colony of Virginia.

John Thomas Rolfe was among those killed.

1624 - Shirley Hundred Massacre

Lord de la Warr (for whom the state of Delaware, as his name was pronounced, took its name) started extensive tobacco cultivation on Shirley Hundred to supply both England and her colonies. Following his death, the land was divided up and by 1624 ‘West and Shirley Hundred’ had been divided into several plantations spread through the now separate ‘West Hundred’ and 'Shirley Hundred'.

Captain Isaac Maddeson

was killed here by Indians while in the militia that was raised after the Indian Massacre of 1622.

1691 - Nute Massacre

Captain James S Nute was killed by indians in 1691 in Dover, New Hampshire.

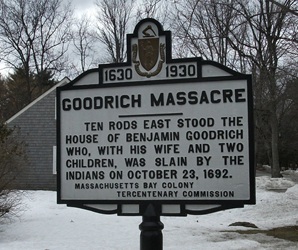

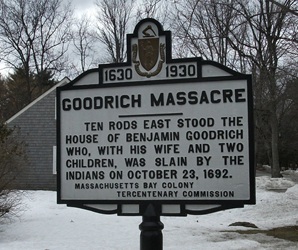

1692 - Goodridge/Goodrich Massacre

Benjamin Goodridge was  shot while praying with his family on a Sabbath evening in Ipswich, Massachusetts. His wife and two daughters were killed by the Indians. Deborah, aged 7 years was taken captive, but was redeemed the next spring at the expense of the Province.

shot while praying with his family on a Sabbath evening in Ipswich, Massachusetts. His wife and two daughters were killed by the Indians. Deborah, aged 7 years was taken captive, but was redeemed the next spring at the expense of the Province.

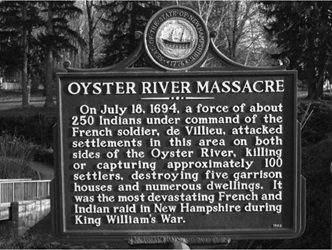

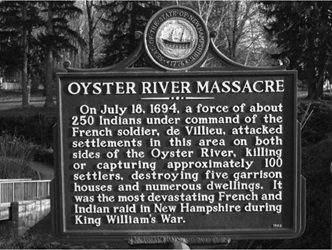

1694 - Oyster River Massacre

On July 18, 1694,  during King William's War, a force of about 250 Indians under the command of a French Soldier, de Villieu, attacked settlements in this area on both sides of the Oyster River, killing or capturing approximately 100 settlers, destroying five garrison houses and numerous dwellings. It was the most devastating French and Indian raid in New Hampshire.

during King William's War, a force of about 250 Indians under the command of a French Soldier, de Villieu, attacked settlements in this area on both sides of the Oyster River, killing or capturing approximately 100 settlers, destroying five garrison houses and numerous dwellings. It was the most devastating French and Indian raid in New Hampshire.

James Bunker III helped defend the Bunker Garrison and survived the attack.

1723 - Vaughan's Island Massacre

Nicholas Barto was killed by Indians on Vaughan's Island, Maine.

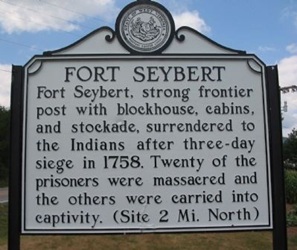

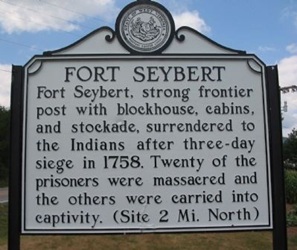

1758 - Fort Seybert Massacre

Roger Dyer  moved his family from Pennsylvania to Virginia around 1747. In the spring of 1758 raiding parties of Shawnese were spotted in the area. Many of the inhabitants went to Seybert's Fort for safety. In late April, the Shawnee raiding party attacked another fort, killing all of the residents. They then went to Seybert's Fort and surrounded it. After a short fight, Capt. Seybert made an agreement with Killbuck, the Shawnee leader, that all would be spared. Upon the surrender Killbuck went back on his word and killed many of the people of the fort. It is believed that Hannah Smith Dyer, Rogers wife, managed to hide in the woods with some children, or she was off visiting family it is unknown as to where she was during the attack. Roger was killed and James the youngest son was taken by the Shawnese as a captive.

moved his family from Pennsylvania to Virginia around 1747. In the spring of 1758 raiding parties of Shawnese were spotted in the area. Many of the inhabitants went to Seybert's Fort for safety. In late April, the Shawnee raiding party attacked another fort, killing all of the residents. They then went to Seybert's Fort and surrounded it. After a short fight, Capt. Seybert made an agreement with Killbuck, the Shawnee leader, that all would be spared. Upon the surrender Killbuck went back on his word and killed many of the people of the fort. It is believed that Hannah Smith Dyer, Rogers wife, managed to hide in the woods with some children, or she was off visiting family it is unknown as to where she was during the attack. Roger was killed and James the youngest son was taken by the Shawnese as a captive.

1759 - Kerr Creek Massacre

On 10 October 1759,  near Big Spring in Virginia, a band of Shawnee Indians coming over the mountains from the Ohio surprised the fort and killed from fifty to sixty persons. This was the last attack by Indians upon the white settlers in this section of Virginia.

near Big Spring in Virginia, a band of Shawnee Indians coming over the mountains from the Ohio surprised the fort and killed from fifty to sixty persons. This was the last attack by Indians upon the white settlers in this section of Virginia.

John Gilmore was among the people killed.

1781 - Hayes Station Massacre

Maj. William “Bloody Bill” Cunningham and a large force of Loyalist militia attacked a group of Patriot militia that were resting in the home of their commander, Col. Joseph Hayes. The Patriots surrendered when the home was set on fire. Bloody Bill then lived up to his name by personally killing every prisoner in cold blood.

On November 19,  Maj. William Cunningham crossed the Saluda River and headed to Hayes Station. The station was at Edgehill Plantation and was commanded by Col. Joseph Hayes. Hayes had been warned of the prsence of Cunningham's force, but after a scouting expedition returned with no evidence of Loyalist activity, he refused to heed any warning.

Maj. William Cunningham crossed the Saluda River and headed to Hayes Station. The station was at Edgehill Plantation and was commanded by Col. Joseph Hayes. Hayes had been warned of the prsence of Cunningham's force, but after a scouting expedition returned with no evidence of Loyalist activity, he refused to heed any warning.

Joseph Hayes owned a tavern adjacent to Edgehill Station - a stop along the local stage coach line. He and about two dozen of his men were sitting down to a nice meal when a colleague, Capt. John Owens, rode up and informed the men that smoke was coming out of the nearby plantation house of the late Brig. Gen. James Williams' widow.

Hayes and his men jumped up from their meal and followed Capt. Owens out of the tavern and up a small hill to gather at an old Cherokee War Block House - to see what was going on at the neighbor's home. They were instantly surrounded by "Bloody Bill" Cunningham with about 300 Loyalists. Hayes and his men ran into the small block house, but it was soon torched, so they threw down their arms and surrendered.

Cunningham warned Hayes that if any shots were fired at his men that all of the station's defenders would be killed. As the Loyalists approached the station, several shots were fired at them. Cunningham sent in a flag of truce and stated that if the post surrendered, he would spare the defenders. Hayes refused to surrender, thinking that reinforcements would be arriving soon. The fight continued for several hours until the post's roof was set on fire by flaming arrows. Choking from the fire's smoke, Hayes surrendered.

Only 2 of the 16 Patriots were killed during the fight. Each man was forced to back out of the small block house to have their hands tied behind them then affixed to a long rope, ostensibly to be marched to another location. However, as soon as the last man was attached to the long rope, Cunningham strarted hanging them, and then his men dismembered fourteen of them, with Cunningham killing 4 Patriots with his sword. Cunningham then rode off, leaving the body parts scattered.

Colonel Benjamin Lewis Goodman, Major Daniel Williams, Joseph Williams were among the Patriots killed.

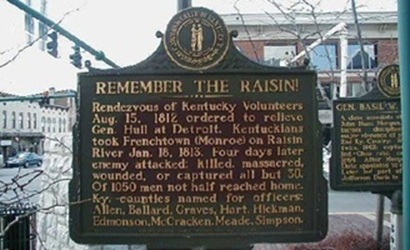

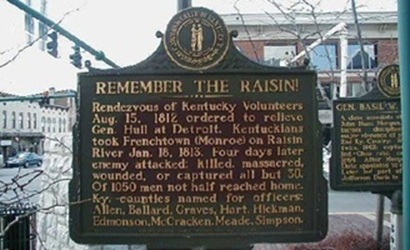

1813 - River Raisin Massacre

The second part of the Battle of Frenchtown was known as the "River Raisin Massacre". It was a severe defeat for the Americans during the war while attempting to retake Detroit early in 1813.

On January 22, the main British/Indian force arrived at Frenchtown. Winchester's headquarters were far away from the main American lines and was no where near his troops when the British attacked.

The British/Indian attack surprised the American camp but they took their positions quickly and returned fire.

However, when the right flank gave way the main line began to retreat, even though the left flank anchored in a fort still held. Winchester, attempting to join the front lines, was captured en route by Chief Roundhead. The American retreat quickly became a rout and only 33 of the 400 engaged escaped the battlefield.

Proctor  feared that Harrison's force might close in on him and made a hasty withdrawal to Brownstown on January 23. Proctor did not have enough sleighs to carry the wounded American prisoners and left them behind under the guard of the First Nations Indians along the River Raisin. The Indians then proceeded to execute 60 American prisoners and ransom off the few unharmed prisoners in Detroit. This action became known as the "River Raisin Massacre."

feared that Harrison's force might close in on him and made a hasty withdrawal to Brownstown on January 23. Proctor did not have enough sleighs to carry the wounded American prisoners and left them behind under the guard of the First Nations Indians along the River Raisin. The Indians then proceeded to execute 60 American prisoners and ransom off the few unharmed prisoners in Detroit. This action became known as the "River Raisin Massacre."

Because of the poor state of readiness of the American troops, they suffered such vast losses, and thus the battle is also known as the "River Raisin Massacre." Harrison retreated up the Maumee River, but when he learned that the British did not pursue, he returned to the shore of Lake Erie and built a fort which he named Fort Meigs.

The defeat at Frenchtown ended Harrison's campaign against Detroit. He instead assumed a defensive position in Ohio and built Fort Meigs. The phrase "Remember the River Raisin" became a rallying cry for Kentucky militiamen.

John Hood was among the Americans killed.

1852 - Oatman Massacre

In 1852, Captain Andrew Dever Cathey  led a wagon train of about 20 wagons, to California from Fort Smith, Arkansas. Along the route, they saw a wagon where the Oatman family had been massacred by Indians. All were killed, except two little girls who were captured by the Indians and a little boy who was left for dead. One of the girls died in captivity and the other was sold to the Mohaves. The boy that survived was instrumental in rescuing his sister, Olive Oatman, and she later wrote a book about the massacre.

led a wagon train of about 20 wagons, to California from Fort Smith, Arkansas. Along the route, they saw a wagon where the Oatman family had been massacred by Indians. All were killed, except two little girls who were captured by the Indians and a little boy who was left for dead. One of the girls died in captivity and the other was sold to the Mohaves. The boy that survived was instrumental in rescuing his sister, Olive Oatman, and she later wrote a book about the massacre.

1863 - Wilson Massacre

An unusual group assembled at the Pulliam farm in southwestern Ripley County, Missouri for Christmas in 1863. Nearly 150 officers and men of the Missouri State Guard's 15th Cavalry Regiment (Confederate); at least sixty civilians, many of them women and children; and 102 prisoners, officers and men of Company C, Missouri State Militia (Union).

The civilians were family members, friends, and neighbors. Confederate "hosts" and Union "guests" were all Missourians; but they were divided by perhaps the bitterest of all enmities-those of civil war.

The day's activity was to begin with religious services conducted by the Reverend Colonel Timothy Reeves, commanding officer of the 15th Cavalry and a Baptist preacher of Ripley County. Then would follow Christmas dinner in the afternoon. The group at Pulliam' s farm numbered above three hundred at the very least, if the figures on the record are to be believed. It was too many for a mere religious service and holiday dinner. Pulliam's was one of Reeves's regimental camps.

What began as a festive occasion ended in horror and tragedy. As the celebrants sat at dinner, their arms stacked, they were surprised by two companies of the Union Missouri State Militia, more than 200 mounted cavalrymen. Only those guarding the prisoners, about 35 men, were armed. The Militia attacked without warning, shooting into the crowd, attacking with sabers, and killing at least thirty of the Confederate men instantly and mortally wounding several more. According to local tradition, many--perhaps most---of the civilians were killed or wounded as well.

The Union force had no casualties, suggesting the possibility that the Confederates may not have fired a shot. The survivors--some 112 officers and men, with their horses, arms, and equipment--were captured and taken out of the War for good, some to die in prison. Colonel Reeves, however, escaped.

The official report of the Union Commander, Major James Wilson, confirms the quick, bloody character of the event: "I divided my men into two columns and charged upon them with my whole force. The enemy fired, turned, and threw down their arms and fled, with the exception of 30 or 35 and they were riddled with bullets or pierced through with the saber almost instantly." Wilson's account did not explain why, if the enemy fired, no bullet shot at point-blank range found its mark; nor, if the rest "fled," why they were all captured. Neither did Wilson mention the presence of civilians, nor harm done to them.

The Union force was a quick-moving raiding party, sent out on December 23 from the Union stronghold at Pilot Knob in Iron County, some eighty miles to the north. Their purpose: recapture of the Union prisoners. They retired the next morning taking the freed personnel of Company C, MSM, and the new Confederate captives of the 15th Cavalry, MSG.

The stunned survivors were left to bury the dead and reflect on the carnage.

Mary E Keel was one of the civilian casualties.

Ambushes

1863 - William Mathes

William Nelson Mathes was born in 1828, and he was murdered in Douglas County, Missouri in 1864 during the Civil War, by Missouri bushwhackers.

Wiliam married Elizabeth Anabell Sutterfield, and they had two sons, Samuel and John Allen. When John Allen was about three years old, a group of renegades posing as northern soldiers began to terrorize the area. This was at the time of the Civil War and feelings ran high. Since the Mathes family were natives of Tennessee, they were targets of this harassement.

After these renegades burned the home of the Mathes family, the family gathered a few housekeeping things from friends and relatives and set up housekeeping again.

A second time they were burned out, William sent the family to relatives in Reynolds County, Missouri for safety. Shortly thereafter, William was taken into the nearby woods and tortured. As a result of this brutal treatment, he died in 1864.

1865 - Thomas Williams

The earliest known organized resistance to secession in Arkansas came when Unionists in Conway County and neighboring counties of the Arkansas Ozarks formed underground peace societies, as they called them, in the fall of 1861.

But the likely leader of the county's resistance faction was Captain Thomas Jefferson 'Jeff' Williams, a  Disciples of Christ preacher, who had ties with several leaders of the society (also Disciples preachers) in neighboring Van Buren County. A small farmer and staunch Unionist in the county's northernmost township, Lick Mountain, Williams was typical of the yeoman hill farmers mobilized for the first time in their lives into political action by the secession crisis.

Disciples of Christ preacher, who had ties with several leaders of the society (also Disciples preachers) in neighboring Van Buren County. A small farmer and staunch Unionist in the county's northernmost township, Lick Mountain, Williams was typical of the yeoman hill farmers mobilized for the first time in their lives into political action by the secession crisis.

In April 1862, Williams organized a band of relatives and neighbors in northern Conway County to resist the Confederate Conscription Act, which made military' service compulsory for men aged eighteen to thirty-five. Two new rebel companies were raised in the county.

Just as Williams organized his Union band in Conway County, General Samuel Curtis marched a large Union force from Missouri south along the White River into Arkansas, arriving in Batesville in early May. Williams and about seventy Union men made their way through rebel lines from Conway County to Curtis's camp and there joined the Union army. Mustered into service as Company B of the First Arkansas Infantry Battalion, these farmers from the northern hills were the first citizens of Conway County to wear the Union blue. The men elected Thomas Jefferson Williams as their captain and his son, Nathan, as second lieutenant. They marched off with Curtis’s army to Helena.

Williams’s main foe was Colonel Alan R. Witt, who led a band of ragtag Confederates based around Quitman (Cleburne County), located about twenty miles east of Williams's farm near present- day Center Ridge (Conway County). In the last two years of the war, Witt's and Williams's companies waged an on-going feud, as did families in the area known to be sympathetic to either side.

During the night of February 12, 1865, Witt’s rebel guerrillas surrounded the home of Captain Williams and called for him to come out. Turning to his wife, Margaret, Williams said, "My time has come." The rebels shot him dead as he opened the door. The vendetta waged by the Williams clan against the rebels who had killed the captain would not end for years afterward.

Indian massacre of 1622 took place in the English Colony of Virginia on March 22, 1622. The English explorer Captain John F Smith, though he was not an eyewitness, wrote in his History of Virginia that warriors of the Powhatan "came unarmed into our houses with deer, turkeys, fish, fruits, and other provisions to sell us." They then grabbed any tools or weapons available and killed all of the English settlers they found, including men, women, and children of all ages. Opechancanough, paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy, led a series of co-ordinated surprise attacks that ended up killing a total of 347 people, a quarter of the population of the Colony of Virginia.

Indian massacre of 1622 took place in the English Colony of Virginia on March 22, 1622. The English explorer Captain John F Smith, though he was not an eyewitness, wrote in his History of Virginia that warriors of the Powhatan "came unarmed into our houses with deer, turkeys, fish, fruits, and other provisions to sell us." They then grabbed any tools or weapons available and killed all of the English settlers they found, including men, women, and children of all ages. Opechancanough, paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy, led a series of co-ordinated surprise attacks that ended up killing a total of 347 people, a quarter of the population of the Colony of Virginia.

shot while praying with his family on a Sabbath evening in Ipswich, Massachusetts. His wife and two daughters were killed by the Indians. Deborah, aged 7 years was taken captive, but was redeemed the next spring at the expense of the Province.

shot while praying with his family on a Sabbath evening in Ipswich, Massachusetts. His wife and two daughters were killed by the Indians. Deborah, aged 7 years was taken captive, but was redeemed the next spring at the expense of the Province. during King William's War, a force of about 250 Indians under the command of a French Soldier, de Villieu, attacked settlements in this area on both sides of the Oyster River, killing or capturing approximately 100 settlers, destroying five garrison houses and numerous dwellings. It was the most devastating French and Indian raid in New Hampshire.

during King William's War, a force of about 250 Indians under the command of a French Soldier, de Villieu, attacked settlements in this area on both sides of the Oyster River, killing or capturing approximately 100 settlers, destroying five garrison houses and numerous dwellings. It was the most devastating French and Indian raid in New Hampshire. moved his family from Pennsylvania to Virginia around 1747. In the spring of 1758 raiding parties of Shawnese were spotted in the area. Many of the inhabitants went to Seybert's Fort for safety. In late April, the Shawnee raiding party attacked another fort, killing all of the residents. They then went to Seybert's Fort and surrounded it. After a short fight, Capt. Seybert made an agreement with Killbuck, the Shawnee leader, that all would be spared. Upon the surrender Killbuck went back on his word and killed many of the people of the fort. It is believed that Hannah Smith Dyer, Rogers wife, managed to hide in the woods with some children, or she was off visiting family it is unknown as to where she was during the attack. Roger was killed and James the youngest son was taken by the Shawnese as a captive.

moved his family from Pennsylvania to Virginia around 1747. In the spring of 1758 raiding parties of Shawnese were spotted in the area. Many of the inhabitants went to Seybert's Fort for safety. In late April, the Shawnee raiding party attacked another fort, killing all of the residents. They then went to Seybert's Fort and surrounded it. After a short fight, Capt. Seybert made an agreement with Killbuck, the Shawnee leader, that all would be spared. Upon the surrender Killbuck went back on his word and killed many of the people of the fort. It is believed that Hannah Smith Dyer, Rogers wife, managed to hide in the woods with some children, or she was off visiting family it is unknown as to where she was during the attack. Roger was killed and James the youngest son was taken by the Shawnese as a captive. near Big Spring in Virginia, a band of Shawnee Indians coming over the mountains from the Ohio surprised the fort and killed from fifty to sixty persons. This was the last attack by Indians upon the white settlers in this section of Virginia.

near Big Spring in Virginia, a band of Shawnee Indians coming over the mountains from the Ohio surprised the fort and killed from fifty to sixty persons. This was the last attack by Indians upon the white settlers in this section of Virginia.

Maj. William Cunningham crossed the Saluda River and headed to Hayes Station. The station was at Edgehill Plantation and was commanded by Col. Joseph Hayes. Hayes had been warned of the prsence of Cunningham's force, but after a scouting expedition returned with no evidence of Loyalist activity, he refused to heed any warning.

Maj. William Cunningham crossed the Saluda River and headed to Hayes Station. The station was at Edgehill Plantation and was commanded by Col. Joseph Hayes. Hayes had been warned of the prsence of Cunningham's force, but after a scouting expedition returned with no evidence of Loyalist activity, he refused to heed any warning. feared that Harrison's force might close in on him and made a hasty withdrawal to Brownstown on January 23. Proctor did not have enough sleighs to carry the wounded American prisoners and left them behind under the guard of the First Nations Indians along the River Raisin. The Indians then proceeded to execute 60 American prisoners and ransom off the few unharmed prisoners in Detroit. This action became known as the "River Raisin Massacre."

feared that Harrison's force might close in on him and made a hasty withdrawal to Brownstown on January 23. Proctor did not have enough sleighs to carry the wounded American prisoners and left them behind under the guard of the First Nations Indians along the River Raisin. The Indians then proceeded to execute 60 American prisoners and ransom off the few unharmed prisoners in Detroit. This action became known as the "River Raisin Massacre." led a wagon train of about 20 wagons, to California from Fort Smith, Arkansas. Along the route, they saw a wagon where the Oatman family had been massacred by Indians. All were killed, except two little girls who were captured by the Indians and a little boy who was left for dead. One of the girls died in captivity and the other was sold to the Mohaves. The boy that survived was instrumental in rescuing his sister,

led a wagon train of about 20 wagons, to California from Fort Smith, Arkansas. Along the route, they saw a wagon where the Oatman family had been massacred by Indians. All were killed, except two little girls who were captured by the Indians and a little boy who was left for dead. One of the girls died in captivity and the other was sold to the Mohaves. The boy that survived was instrumental in rescuing his sister,  Disciples of Christ preacher, who had ties with several leaders of the society (also Disciples preachers) in neighboring Van Buren County. A small farmer and staunch Unionist in the county's northernmost township, Lick Mountain, Williams was typical of the yeoman hill farmers mobilized for the first time in their lives into political action by the secession crisis.

Disciples of Christ preacher, who had ties with several leaders of the society (also Disciples preachers) in neighboring Van Buren County. A small farmer and staunch Unionist in the county's northernmost township, Lick Mountain, Williams was typical of the yeoman hill farmers mobilized for the first time in their lives into political action by the secession crisis.